Harvey Bentley and the African American “Get-To-Gether” Picnics

Never underestimate the power of a public park picnic. Organized by Harvey Bentley and other influential Black leaders during the Great Depression of the 1930s, the "Get-to-Gether" picnics were a way for the African American community to improve social bonds not only across eastern South Dakota but all over the Midwest.

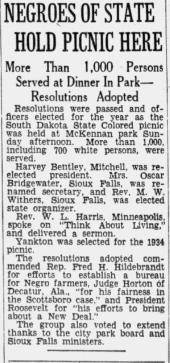

In 1933, Harvey Bentley walked around McKennan Park for the annual African American “Get-to-Gether” picnic. He could smell the sweet aroma of barbecue spare ribs and fried chicken spread over tables and could barely hear over the joyous chatter of over a thousand people, Black and White, enjoying their meals. While walking around he could hear different conversations about Franklin D. Roosevelt's New Deal programs, which attendees endorsed with a resolution. During this time, Bentley served as the president of the South Dakota Colored Picnic Association. Due to the isolated settlement of African Americans across the upper Midwest, the Black community organized the “Get-to-Gether” picnics in Sioux Falls and around eastern South Dakota, helping to improve social bonds across the region.

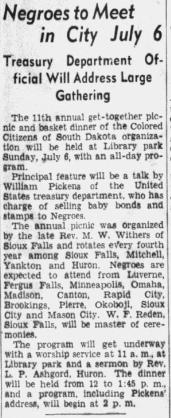

In the 1930s, the Black community of South Dakota was spread thin across the state with some of the larger communities in Yankton, Mitchell, and Sioux Falls. In the midst of the Great Depression, one-half of the U.S. populace was either unemployed or underemployed, but African Americans were often the first fired and last hired. Economic instability was compounded by the threat of racial violence as the Ku Klux Klan formed in South Dakota in 1921, marching in a downtown Sioux Falls parade in 1924. To counteract precarious social positions, African Americans like Rev. Mathew Withers of St. John’s Baptist Church, Harvey Bentley, and Louisa and Harvey Mitchell, decided that they needed to be more cohesive as a group to help the community survive. They came up with many different ways in which they could become close-knit for self-reliance, but one way was the “Get-to-Gether” picnic that began in Mitchell, South Dakota, in 1930. Their idea was to get the relatively isolated African American population in South Dakota a place to get together once a year to discuss things happening around the region and the nation. After a successful first picnic, it was suggested to not only bring the picnic to Sioux Falls but also rotate it between Sioux Falls, Mitchell, Huron, and Yankton every four years, with the Withers, Bentley and the Mitchells serving as chief organizers.

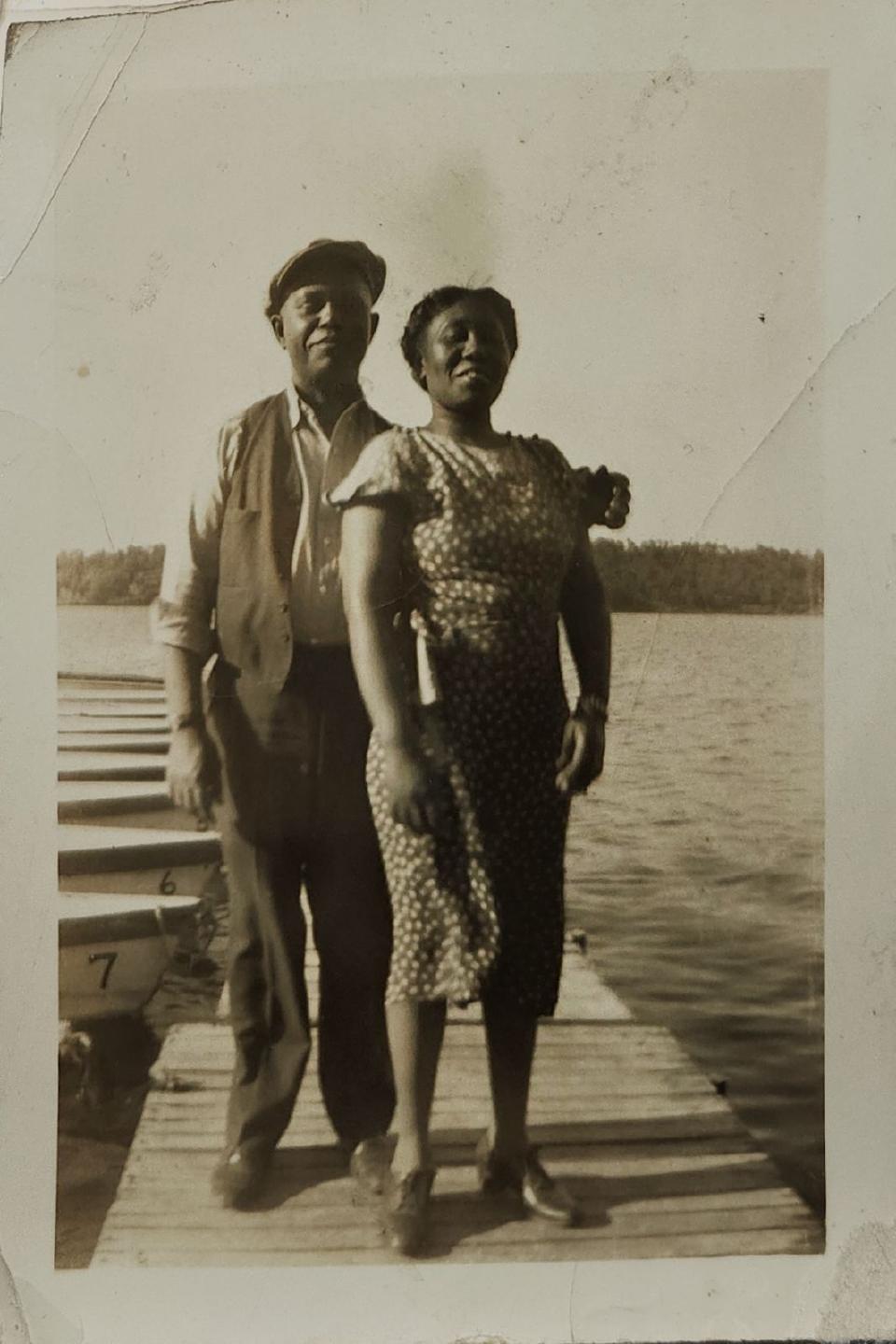

Harvey Bentley served as state president of the South Dakota Colored Picnic Association for twenty-five years. Born in Salisbury, Missouri, on August 6, 1897, Bentley moved to South Dakota at eighteen years old, living in Yankton, then Mitchell, and finally in Sioux Falls. While he lived in Yankton, he joined the U.S. Army during World War I and fought overseas in France. After his military service, Bentley moved from Yankton to Mitchell, and later married LaBerta Smith in 1935. Bentley held a variety of occupations, such as a barber, a fireman, and working for the Kreiser Surgical Supply Co. for over twenty years before retiring.

As the annual picnics grew in popularity during Bentley’s tenure, they drew in other African American communities from Midwestern states like Nebraska, Minnesota, Iowa, and North Dakota. When the picnic was held in Sioux Falls, it was held at a city park, which was typically Library (now Heritage) Park or McKennan Park, as an open area that could hold different activities. Parks and other recreational areas were used in multiracial cities like Louisville, Kentucky, to challenge segregation of public accommodations. At each picnic, the program included events such as a morning worship service, a basket lunch, a speech about the African American community, and discussion of national issues. It sometimes featured a special event like a 30-voice choir and band or the 929th Squadron presenting a special drill. From the Great Depression through World War II, picnic events often reflected national concerns. During the 1930s, there were speeches by members of the community talking about how Black people could get federal New Deal jobs, as well as how to achieve the goal of desegregation. After 1941, the picnic goers supported the war effort by providing booths to buy war bonds. The Black USO Center also introduced African American soldiers stationed at the Army Air Force Technical School in Sioux Falls as a way to introduce newcomers to the community.

The “Get-to-Gether” picnics occurred from 1930 until the 1960s with the last record of the picnic being in 1962. Given the picnics' wide community support, the reason for their end isn’t clear. One reason might have been the Black community felt racial progress from the Civil Rights Movement and didn’t feel the need for the picnics to happen anymore. Another reason could have been that a majority of the founding members of the picnic had retired or died. Still another reason might be feeling less isolated as Black communities grew in size during World War II. Regardless of why the picnics stopped, they helped create social bonds between Black people across eastern South Dakota and the Midwestern region.

Images