Booker T. Washington Service Center

The Booker T. Washington Service Center was created by Sioux Falls’ Black community as lodging for black travelers and newcomers to the city at a time when racial segregation made hotels unavailable. Active from 1926 to 1957, it enjoyed great success not just as housing, but also as a community gathering center. When tracking the Center's shifting status over time, though, one accomplishment stands out among the rest: its closing.

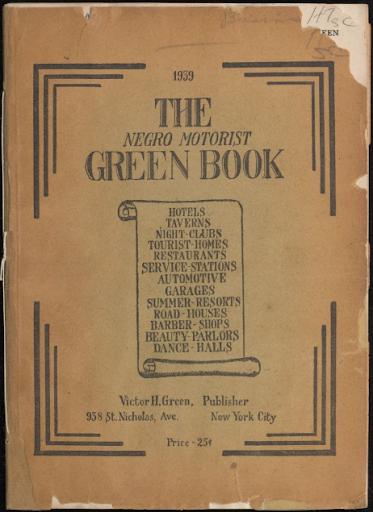

The Negro Motorist Green Book, edited by Harlem-based postal carrier Victor Hugo Green, provided African American travelers with a guide to places they could stop–hotels, restaurants, service stations–without fear of racial prejudice or harassment. While the 1939 edition featured safe establishments in segregationist strongholds from Mississippi to Missouri, it also listed two “tourist homes'' in Sioux Falls, South Dakota: “Mrs. J. Moxley” at 915 N. Main Ave. and “Service Center'' at 415 S. 1st Ave. It was referring to the Booker T. Washington Service Center. In 1947, Harvey Bentley told the local newspaper that one of the Center’s goals was “to provide housing for colored folks who, while traveling through here, can’t get hotel lodging.” Bentley continued: “Sioux Falls has the reputation of being the most prejudiced town in the state. I don’t like to say so, but it’s the truth.” The Center embodied its namesake’s philosophy of racial uplift through accommodation by fulfilling a need for temporary lodging and a recreational space within the Black community of the Sioux Falls area.

In contrast to many of his contemporaries like W.E.B. Du Bois, who called for direct action over civil rights, Booker T. Washington believed that racial equality would be more easily obtained when Black people focused first on developing job skills and economic power. Although the success of this approach was felt throughout the years the Center was open, as evidenced by newspaper articles lauding the local Black community for its successful business owners and educated children, its largest success was ultimately felt when the Center closed.

The Booker T. Washington Service Center was housed in many different buildings over the years. In 1926, the first location was opened at 313 S. First Ave. Within a few years, it expanded and was moved to a new building at 415 S. First Ave to be able to accommodate more people. In January 1932, this second location burned down, and operations were temporarily moved into the home of African American community leaders Harvey and Louisa Mitchell. A new, larger location was built at 718 S. 2nd Ave that summer. The Center again moved In 1948 to 702 E. 6th St., where it remained until it was closed in 1957.

Throughout the time it was open, the Booker T. Washington Service Center served as transitional housing for Black newcomers, where they could stay while searching for their own residence. Maurice Coakley, who would grow to be a prominent voice for civil rights in Sioux Falls, was one such guest. Ten to fifteen people could be accommodated on rollaway beds each night. In the year 1936 alone, the Center provided transitional housing for 74 African Americans.

The Booker T. Washington Service Center also lodged Black travelers visiting Sioux Falls, including actors, athletes, musicians, and maids and chauffeurs who were accompanying their White employers. One example is the Wings Over Jordan Choir, based out of Minneapolis, Minnesota, and directed by Rev. Glenn T. Settle, who stayed at the Center in 1951. Arnold Green, then the only Black member of the Sioux Falls Canaries baseball team, stayed that same year. Travelers were directed to the Center by signs in train stations and bus depots, as well as by the Negro Motorist Green Book, a national guidebook of businesses that would serve Black roadtrippers.

In addition to housing, the Booker T. Washington Service Center was also an important social and recreational space. It hosted political meetings with keynote speakers. The Sioux Falls chapter of the NAACP held their meetings in the main room, as did social groups like the Colored Women’s Federated Club and the Bronze Women’s Club. When the South Dakota Education Association held its annual conferences in Sioux Falls, the Center served as a sort of “headquarters” for Black educators. Each week, Sunday school and choir practices were held in cooperation with St. John’s Baptist Church. Community members were always welcome over for bridge games, birthday parties, or even just meals.

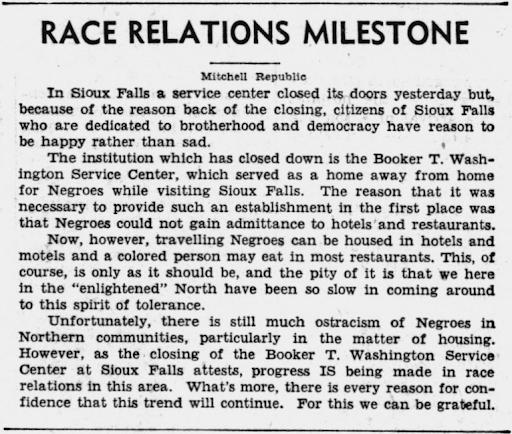

Its popularity aside, the Booker T. Washington Service Center eventually closed in 1957, when it was decided that there was no longer a need for it. With desegregation among the city’s establishments, the Black community was able to stay in hotels and be served at restaurants. Social clubs like the Boys Scouts and Girl Scouts were also racially integrated.

Images